The Afterlife of Evidence

Several years ago, I asked a question that most scholars of the laws of evidence would not ask. That question was, at the conclusion of legal proceedings, where does the evidence go? Socio-Legal Studies demand that we understand how legal processes and materials shape the world. ‘Evidence’ means different things to legal professionals, litigants, police, journalists, and the public. It means something else to crime victims and their loved ones. Court registrars, archivists, and record-keepers have distinct relations with, and responsibilities for, evidentiary materials. For Socio-Legal Studies, important work in this field is done by scholars of open justice, transparency, and accountability. However, there are other socio-cultural contexts in which evidence matters. The appearance of evidentiary materials in cultural contexts transforms our expectations of journalism, government disclosure, dignity and privacy. Citizen-made footage and imagery, the notion that anyone can make evidence, shapes our expectations of justice. Access to evidentiary material has provided inspiration for artists, playwrights, and other cultural producers.

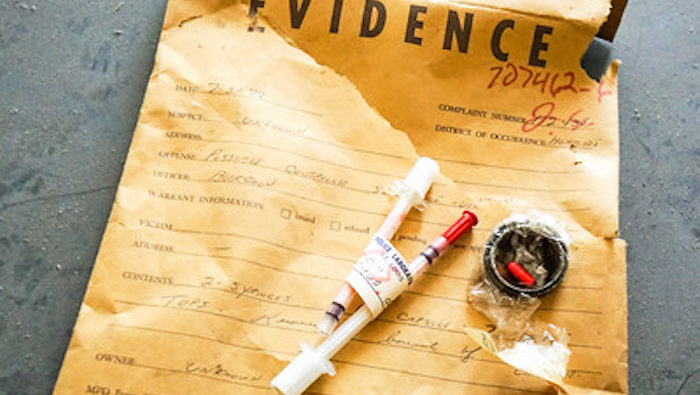

For a long time, I encountered evidentiary materials in unexpected places. Crime scene photographs, mug shots, artefacts, legal records: they were appearing in museums and galleries, coffee table books, artworks, wine labels. These encounters were serendipitous, but also, at times, unsettling. Court proceedings are generally open to the public, but evidence is often adduced to resolve disputes that are traumatic, humiliating, sensitive, and personal.

A friend told me that she had seen an artwork at the Whitney Biennial in 2008. Titled Tearoom (1962/2007), and attributed to William E. Jones, it was 56 minutes of evidentiary footage made by concealed police officers in a men’s public toilet in Mansfield, Ohio, in 1962. The work is silent, covert surveillance footage. It records men’s brief sexual encounters. It was used to secure at least 31 convictions for sodomy. Later, in our correspondence, Jones couldn’t accept my criticism of his appropriation. True, this was lawfully obtained evidence; in the context of an art gallery, however, I felt that the work was sad, humiliating, and warranted better justification for its display. Our disagreement gave me pause.

This was the moment my question transformed into a project.

I became a kind of renegade detective in museums, archives, and retired policemen’s garages. I met artists, novelists, playwrights, curators, conservators, police, lawyers, and judges, and they spoke to me about their own adventures and misadventures with criminal evidence.

Some criminal evidence is traded on the internet; some can be purchased in high-end auction houses. Some of it is cared for by archivists, curators, conservators, and librarians. Clothing, firearms, diaries, photographs. I saw a tiny jar containing maggots removed from a murder victim, used to establish the time of her death. I saw the forensic kit provided to Scottish bus drivers so they could gather saliva after they’d been spat on. The gun that killed Trayvon Martin, sparking the Black Lives Matter movement, was offered for sale online.

Crime’s archive turned out to be more capacious that I imagined. I interviewed Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, victim of Australia’s most notorious miscarriage of justice. Her pathway to justice turned on the forensic re-examination of evidence: baby clothing, camping equipment, the family car.

Once exonerated, the evidentiary materials that had belonged to the family were returned to them. The car was in pieces; the surviving children had outgrown their clothes; many items were covered in forensic markings. There were the garments in which baby Azaria had died. Her shredded diaper. What to do with it? Following the Chamberlains’ exoneration, it was no longer criminal evidence; it was evidence of a miscarriage of justice. The Chamberlains turned over all of these items to the National Library of Australia and the National Museum of Australia.

My journey into the cultural afterlife of evidence is documented in my book In Crime´s Archive. I began to realise that the question – where does evidence go? – had been eclipsed by another one: what even is evidence? Some items are brought into existence solely for an evidentiary use, and some are destroyed at the end of their evidentiary life. My book is interested in crime’s afterlife, the socio-cultural sphere where evidence lingers, spectral and undead.

The idea that law’s processes have an afterlife is the subject of new scholarship in legal studies, criminology and digital media. For Socio-Legal studies, the inquiry into how evidence lives and dies gives rise to new research opportunities. For example, new technologies produce new opportunities for making evidence – police body-worn cameras, mobile phone footage, drones and online surveillance systems – and these demand Socio-Legal and ethical interrogation. New forms of visual evidence also provide new litigation strategies, characterised by spectacle and audio-visual production techniques, transforming courtrooms into theatres or sets; these also demand Socio-Legal examination. In the digital age, the destruction of evidence – whether lawfully or not – requires new methods and personnel, and these also bring challenges for law and ethics, as well as opportunities for creative and timely Socio-Legal inquiry.