The Rule-of-Law Myth and Its Advocates

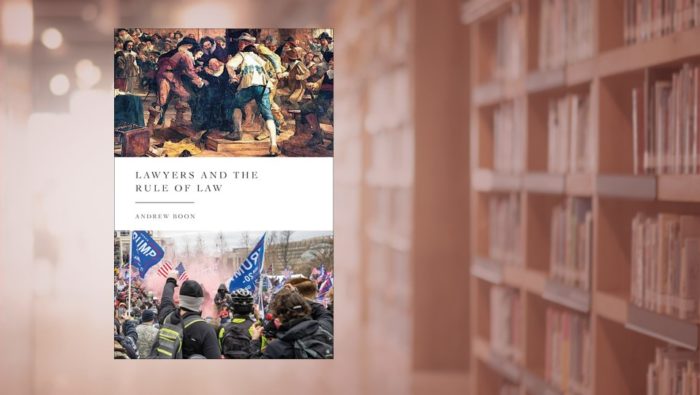

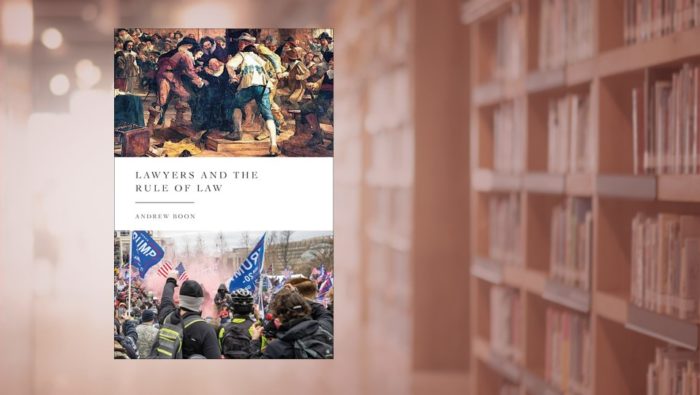

If the rule of law is a myth, then lawyers are the advocates of this myth. In his encyclopaedic book, Lawyers and the Rule of Law, Andrew Boon delivers an unparalleled, comprehensive overview of the relationship between the myth and its creators, tracing its evolution across five ‘core common law jurisdictions’ (p. 421): the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The book is a remarkable accomplishment, encompassing the legal histories of multiple jurisdictions and drawing upon an array of legal, political, and social theories. It also holds significant contemporary relevance, exemplified by discussions of Guantanamo Bay, Brexit, Trump’s impeachment, and the challenges these cases pose to the rule of law, domestically and globally.

The book is divided into four parts: government, practice, profession, and future. Part 1 establishes the philosophical and political foundations of the rule of law as a governance ideal in Western Europe and North America. Part 2 delves into the practice of law, beginning with lawyers’ identities and individualities, and proceeds to discuss the legality and morality of their work. Part 3 examines the legal profession from an organizational perspective, scrutinizing the social structure of the bar and lawyers’ regulations and codes of conduct. Part 4 explores four future trends: two focused on the tension between professionalism and corporate power for lawyers, and the other two on the impact of globalization and democratic backsliding on the rule of law.

In the Epilogue, Professor Boon revisits the legacy of the European Enlightenment and defines the rule of law as ‘about societies governed by law with minimal coercion’ and involving ‘the consent of the governed, secured by striking a balance between a general condition of legality and the rights of the individual’ (p. 474). He further posits that lawyers are ‘the most important promoters of this idea of the rule of law and its vital defenders’ (p. 474). Lawyers in common law countries serve to protect citizens’ rights against the state’s arbitrary power. They are also committed to formal legality and particularly sensitive to procedural justice. The legal profession ‘binds different kinds of lawyers, representing different dimensions of the rule of law’ (p. 475).

This classic liberal view of lawyers and the rule of law has been reiterated by various generations of socio-legal researchers, from classical theorists such as Alexis de Tocqueville and Max Weber to contemporary scholars like Martin Krygier, Terence C. Halliday, and Lucien Karpik. However, it is also an Anglo-American-centric view—an intellectual myth only loosely connected to empirical reality. While lawyers are often promoters of the rule-of-law ideal, as Professor Boon aptly contends, they are not always its defenders. Numerous historical and contemporary cases feature lawyers as accomplices of arbitrary power, such as those aiding the Third Reich in the 1940s or colluding with Trump after the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Many lawyers side with the state rather than opposing it when the political tide turns, even within Anglo-American contexts.

Moreover, the rule of law is an ambiguous and contentious concept, subject to various definitions for scholarly and political purposes. The definition adopted in this book aims to strike a balance between ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ conceptions, yet it remains vulnerable to rigorous empirical inquiry. For instance, the notion of a rule-of-law society ‘governed by law with minimal coercion’ (p. 474) assumes that law itself is not a form of coercion. It overlooks the instrumental aspect of law as a primary governing tool of the coercive state. Societies are invariably divided into complex and often conflicting groups along lines of race, gender, class, and other factors. Achieving the ‘consent of the governed’ necessitates not only the work of lawyers but also political propaganda, cultural clashes, violence, and the work and sacrifice of activists and ordinary citizens. Lawyers are educated to believe they are pioneers of the rule of law, yet many hesitate or even retreat when political upheavals occur.

Consequently, questioning both the rule-of-law myth and the self-proclaimed heroic role of lawyers in shaping legal orders would yield more grounded and insightful perspectives on the relationship between the legal profession and the rule of law, in all its complexity. With that in mind, Professor Boon’s book undoubtedly serves as an excellent foundation for a truly global inquiry on this topic. It is now the responsibility of other students of the legal profession to expand its geographic scope and critique its theoretical underpinnings. Despite the book’s accomplishments, the most thrilling work lies ahead of us.