Capturing the Political Character of an Anticorruption Initiative Through Relational Legal Consciousness Research

In 2014, Brazil was shaken by an anticorruption initiative labelled lava jato (car wash). Lava jato began as an ordinary money laundering case but quickly escalated into something much bigger, as investigations unveiled a corruption scheme at the heart of Brazil’s national oil company Petrobras. The CEOs of major construction companies and officials from key political parties were arrested, including Brazil’s current president Lula da Silva.

Lava jato was praised in Brazil and internationally for ending impunity and promoting the rule of law. But, for some observers, this didn’t sit right. They noted that, just as lava jato unfolded, Brazilian politics began drifting toward authoritarianism, culminating with the election of Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency in 2018. In grappling with this apparent paradox, I decided to investigate lava jato as a site of legal consciousness production.

Legal consciousness studies drew from the cultural or interpretive turn in the social sciences to revolutionise law and society studies. Scholars such as Patricia Ewick and Susan Silbey, followed by several others, decided to look at the meanings ordinary people ascribe to law and how these meanings underpin the enduring structure of the rule of law. More recently, scholars have emphasised the importance of understanding the production of legal meanings amid their embedding social interactions. Kathryn Young and later Lynette Chua and David Engel labelled this ‘relational legal consciousness’. Lava jato seemed extremely appropriate for investigation into the relational production of legal meanings and the extent to which they are supportive–or not–to the rule of law.

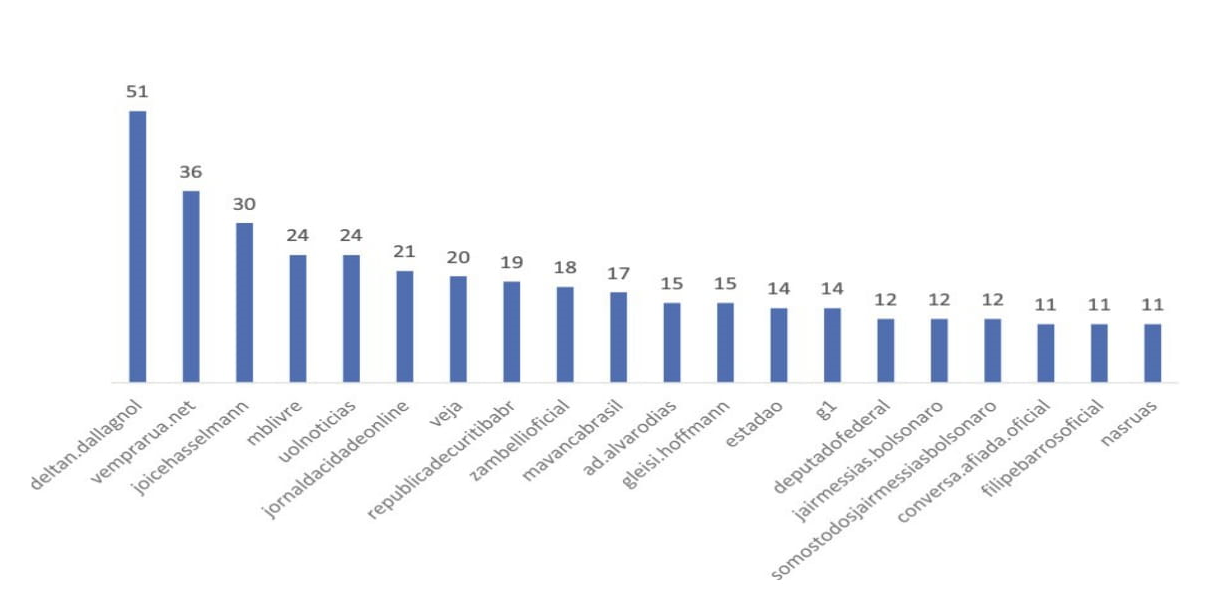

One of the pillars of the lava jato operation was what prosecutors in the case conceived of as transparency. Using press conferences and social media activism on Facebook and Twitter, prosecutors tried to involve the people in every step of their work. I studied Facebook posts with the words lava and jato from 2017–2019, totalling 75,000 posts and their comments. The posts were collected using a paid social media monitoring tool and the comments extracted using the paid tool exportcomments.com, with videos and images being manually downloaded and stored for analysis. Prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol’s page had 53 posts that drew the most engagement in this dataset (n=750), more than any other page in my sample (Fig. 1). These posts attracted 122,335 comments from Facebook users who followed or interacted with him.

Figure 1. The Facebook pages with most posts on lava jato, 2017–2019. Dallagnol had another two posts from his personal account that made it to the top-750.

Considering this corpus of data, I asked: What did those interactions amount to? Did they help nurture a virtuous, civic spirit consistent with the rule of law, or did they produce something different and perhaps more bitter?

My analysis used both quantitative and qualitative techniques. Frequencies for the most-used words in the comments to posts were calculated. Networks of words were mapped, showing which words are connected to one another. This was supplemented with qualitative reading and coding of posts/comments that had at least one like and, therefore, some visibility and resonance. To provide context, this analysis was triangulated with academic and media sources on lava jato.

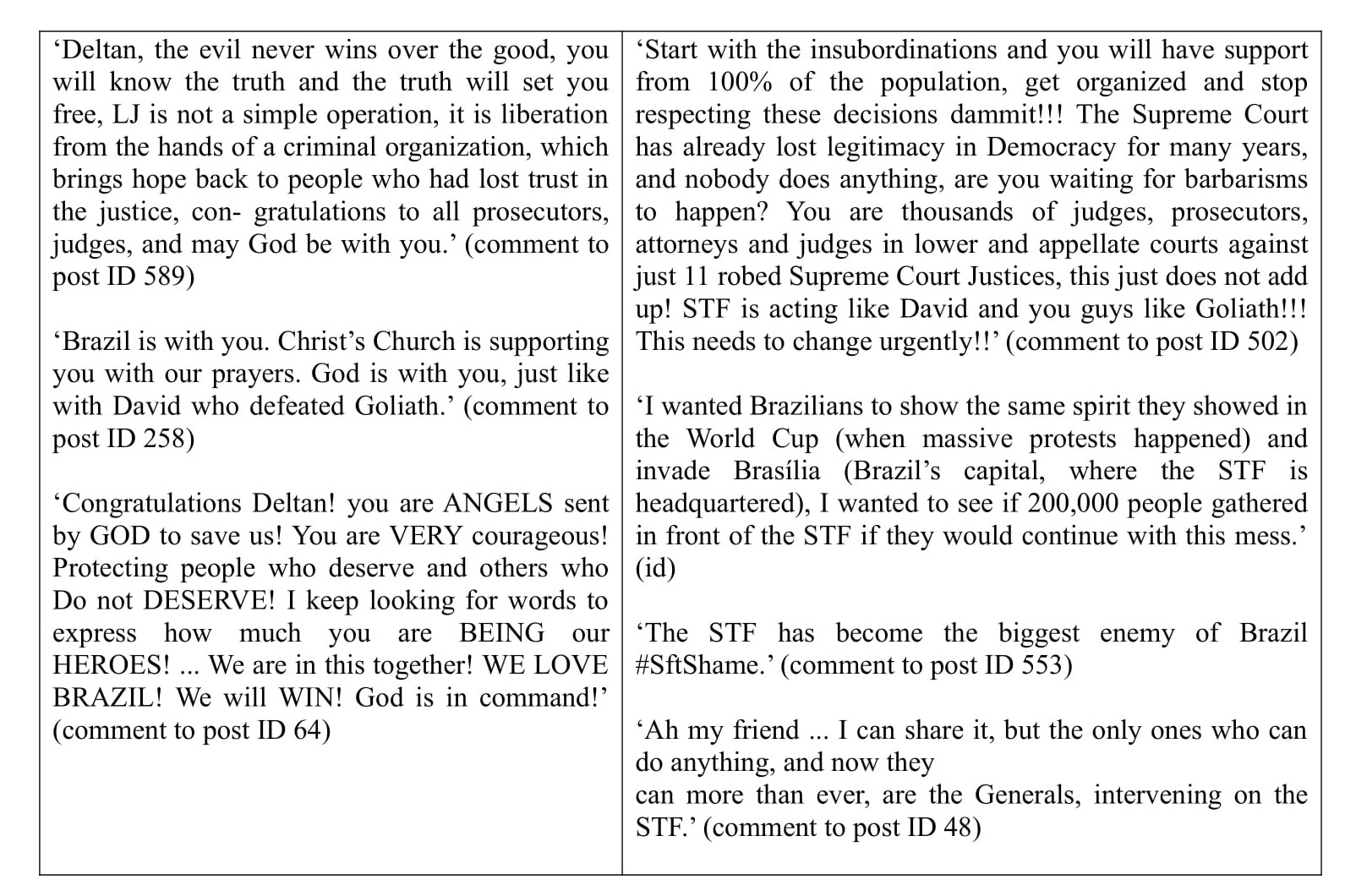

My findings support the more sceptical views of lava jato. The exchanges between lava jato prosecutors and Facebook users coproduced a cultural schema contrary to the rule of law (Fig. 2). Anticorruption work was glorified, construed as messianic or patriotic, not as an institutional endeavour based on, and subject to, rules. Society was called to participate in a fight against corruption that became a crusade against institutions, with systematic attacks on Congress and the Federal Supreme Court (STF). This schema supported people’s mobilisation both online and offline, and may have possibly legitimised the autocratic moves of Bolsonaro, who ran using symbols (the ‘myth’, ready to fight corruption) and a motto (‘Brazil above everything, God above all’) that fully resonated with the stock of meanings (re)produced through lava jato.

Figure 2. Examples of comments/replies to various posts by Deltan Dallagnol.

My findings carry several implications for studies of legal consciousness and anticorruption. Here, I highlight two. Firstly, my findings invite research that takes seriously the role of social media platforms in altering and expanding the space in which Socio-Legal interactions unfold and meaning is given to law. Accordingly, that considers posts, comments, and the like as valid data sources in legal consciousness studies, where traditional qualitative sources, namely in-depth interviews, still predominate. Secondly, my findings stress the importance of research that looks not only at schemata produced in support of the rule of law, but also in its rejection.

Indeed, scholars such as Erik Fritsvold, Simon Halliday and Bronwen Morgan, Marc Hertogh, and myself have identified instances in which subjects understand the rule of law as an inherently corrupt order that they are not willing to support and engage with. We should be meticulously looking at these pockets of legal detraction including the means, digital or otherwise, that are being used to nurture and expand them – at a time when the rule of law consensus is being threatened by rising autocrats.