Access to Justice as a Human Right and the Responsiveness of Law

The fundamental question of whether and how people can enforce their individual rights effectively is still at the core of much Socio-Legal research. As Cappelletti and Garth put it in their seminal EUI study more than four decades ago, equal access to justice can ‘be seen as the most basic requirement – the most basic “human right” – of a modern, egalitarian legal system which purports to guarantee, and not merely proclaim, the legal rights of all’ (1978: 185).

Drawing on some of the preliminary findings of an ongoing study on Access to Justice in Berlin, I argue that a further development of the broader conceptual approach to access to justice is overdue – with regard to its (normative) human rights aspect as well as its empirical side. The independent research project, funded by the Berlin government, has been carried out since October 2020 by a research group at the Social Research Centre Berlin (WZB). It aims to develop, based on empirical enquiry, a deeper understanding of the ways consumer and tenancy rights are mobilised by citizens in Berlin and explore whether their legal needs are effectively addressed and enforced by the judicial system.

During a first exploratory phase, over 40 semi-structured expert interviews were conducted. In a second phase, the results of the exploratory survey were discussed in focus groups with experts from (legal) advice bureaus/centres, judges, and paralegals working in legal application centres at the district courts (Amtsgerichte). Building on a refined set of hypotheses, a range of field observations were carried out at district courts and at various places where Berlin citizens can get gratuitous legal advice (which we generally referred to as Beratungsstellen, ‘advice centres’), as well as additional interviews with practicing lawyers (Rechtsanwälte). In addition to the collection and evaluation of the qualitative data, we did a quantitative analysis of civil law proceedings before Berlin district courts for the years 2017 to 2020. The coded and then anonymised data set (full census) includes all parties involved in the subject areas of ‘tenancy’ and ‘purchase matters’ and thus encompasses approximately 250,000 parties involved in slightly more than 100,000 proceedings. Among other things, we received information on the outcome of the proceedings, legal representation, applications for legal aid (Prozesskostenhilfe – PKH), duration, amount in dispute, onomastic assignment of the name and the postcode of each party to the proceedings.

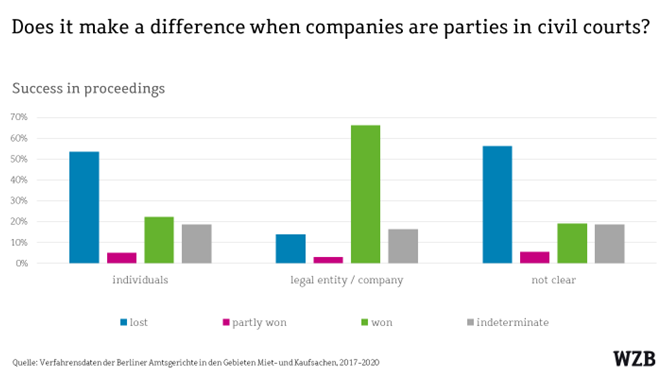

The (preliminary) findings of the quantitative as well as qualitative data are quite astounding. They reveal a picture that largely runs counter to the idea of civil law proceedings as a ‘level playing field’ where both parties have equal chances of successfully litigating and vindicating their rights. The default position in the vast majority of proceedings is asymmetrical. In almost three out of five cases, only one of the parties is represented by a lawyer. This is significant, since the chance of winning a case is, not surprisingly, almost three times higher for the legally represented party. The asymmetry is even stronger where one of the parties is a legal entity or institution, usually a company – in less than fifteen percent of the proceedings we analysed, was the company on the losing side. This again corroborates Galanter’s theoretically founded distinction between one-shotters and repeat players, with the latter being able to ‘play the litigation game differently’ by building on their accumulated experience, knowledge, and litigating power.

Blankenburg once dubbed civil courts ‘service providers for the business world’. This critical assessment of the inequalities in civil law proceedings obviously still holds true today, despite the emergence of new social rights like tenancy and consumer rights in substantive law. As we can see from the data, the current legal aid system in Germany does not appear fit for mitigating the existing economic barriers which socio-economically weaker parties and indigent people face.

I argue that there are two conclusions to be drawn from this. First, we need a more elaborate conceptualisation of the fundamental right to access to justice in the context of new social rights which goes beyond drawing on the case-by-case law of the European Court of Human Rights on Article 6 ECHR. As the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany (FCC) held in a landmark case on Beratungshilfe (legal advice aid), the rule of law more fundamentally demands an “extensive equalisation between the well-off and the poor in the area of legal protection” (para. 30). This should serve as a starting point for exploring the human right to equal access to justice more deeply.

Second, when it comes to empirical research on law, we should investigate and re-conceptualise the notion of ‘responsiveness’, whereby I mean the readiness of the legal system to actually cover and redress the legal needs of people entitled by the law– with regard to our research for instance in housing and consumer issues. This could help with gauging the actual effectiveness of legal provisions which proclaim to endow individuals with enforceable (social) rights. The key question to ask would be whether the legal system is in reality capable of effectively addressing and enforcing the legal needs of people, as it purports to do.

Individual (and also collective) rights which cannot be enforced in practice by those for whom they are intended are worthless. The normative discourse on (‘new’) social rights has largely neglected this. It therefore needs to be supplemented by an interdisciplinary approach that is founded on the notion of equal access to justice as a fundamental right and based on in-depth empirical research.