Stories that Refugee Artworks Tell: Using the ‘Visual’ in Socio-Legal Research

The emancipatory potential of art, voicing the resistance of artmaking individuals, is recognised in much scholarly research. The revelatory potential of art, too, is embraced in certain bodies of literature arguing that art can actually reveal the lived experiences of artmaking individuals for the purposes of research. In this post, I turn to the latter to reflect on a Socio-Legal project in design stage, which explores the use of visual artworks created by refugee artists to comprehend their agency vis-à-vis borders.

The bourgeoning of visual art as data traces back to the development of visual ethnography in anthropology and sociology in the late 1950s. Whereas the incorporation of the visual in legal research, specifically in Socio-Legal Studies, has been slower. Early Socio-Legal engagements with the visual diverge significantly from conventional approaches of law which treats art and law as separate entities. Socio-Legal scholars have recognised the shortcomings in these approaches, such as the doctrinal approach which assesses art as a commodity to be protected by law. Instead, they amalgamate the two entities through pondering what artworks can reveal about law and legal phenomena. Nevertheless, room for development in blending art as a form of data into Socio-Legal Studies remains, especially considering the extent of the ‘visual turn’ in social sciences and humanities.

It took me some years to grasp the nexus between art and legal research, though I consider myself a political cartoonist who has created editorial cartoons since 2007. In 2016, I illustrated a story book, The Journey of Nasim, which I and two colleagues designed for art therapy sessions with Syrian refugee children organised with NGOs in Istanbul, Turkey. The book contains several cultural and allegorical elements, so that children could internalise and feel at ‘home’ in their host society. Translated from Turkish into Arabic, the story narrates an interplanetary journey for finding a new ‘home’ of the protagonist, Nasim (a gender-neutral name used in Syria), and their friend Muhammed Faris. In reality Faris is the first Syrian astronaut, who lives in Turkey as a refugee.

As an undergraduate law student studying refugees displaced due to the Syrian civil war and the Arab Spring, using art (therapy) as a method was useful to circumvent the untold horrific experiences of refugee children. This was particularly important because the children had difficulties expressing themselves due to PTSD. Nonetheless, our study was not without ethical risks and implications, such as respecting children’s best interests as well as understanding their vulnerability and avoiding any potential harm. Addressing these challenges required the involvement of an art therapist during the sessions. Using our illustrated book, the art therapist, with their expertise and experience of approaching children with mental health challenges, enabled the refugee children to elicit their anxieties and experiences of civil war and displacement. In our fieldwork, we discussed with the therapist and NGO representatives the outcome of the sessions to make sense of children’s reflections. Preserving the anonymity of our subjects and interlocutors, we were able to present our findings. We ascertained that art as a method (in collaboration with an art therapist) may enhance interaction with research subjects, thus assist overcoming language and communication barriers that may emerge in an ethnographic project.

Later, throughout my doctoral research project, my insights concerning the intersections of law and the visual suggested that art can reveal the societal impact of law ‘in context’. This is both in the form of data creation and collection through participatory methods with the direct involvement of subjects in the research, or as a form of data through curation by the researcher of the artworks reflecting artmakers’ lived experiences.

Within my doctoral project, six years following my experience in The Journey of Nasim, I am designing an empirical study to recount refugees’ stories reflected in the paintings they create in an art centre run by an NGO, The Hope Project, in the Greek Lesvos Island. I aim to explore how these artworks reveal refugees’ use of their agency to overcome the challenges posed by the manifold forms of borders, such as EU’s hotspot approach. Visual ethnography can provide valuable insights about refugees’ ‘lives as told in their own voices’, such as feelings, thoughts, and memories developed throughout their encounter of displacement and borders. The artworks are accessible online, though potential ethical questions and other dilemmas may concern the artists’ willingness and consent for having their works used for research, as well as preserving their anonymity. Like in most ethnographic projects, contacting the interlocutors, in this case NGO representatives, early enough and designing the project accordingly help elucidating these questions and dilemmas.

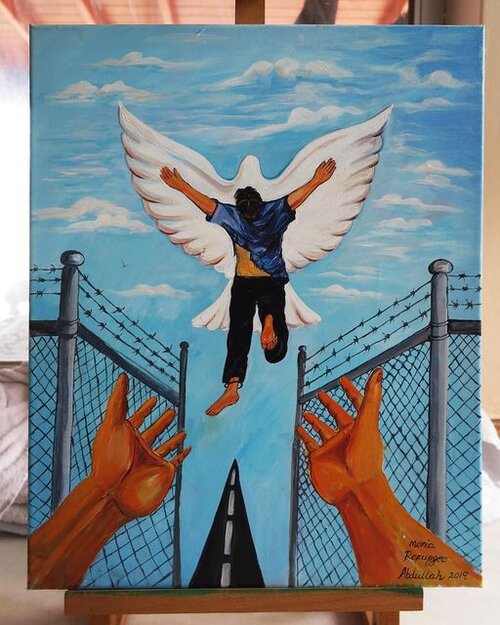

Paintings by Najib Hosseini (above) and Abdullah Rahmani (below) who are Afghan refugees and two of the many brilliant artists that were hosted at the Hope Project Greece in Lesvos. They have kindly given their respective consent for the use of their artworks in this post.

Considering these aspects, my ‘dual role’ as an artist-researcher in employing art as data involves two main components: curating through visual ethnography the artworks that reflect refugees’ visual practices and experiences (data collection), and reflexively interpreting these non-verbal artefacts in view of the relevant societal context within which they are produced (qualitative content analysis), namely ‘explicating explications’. First, I select the artworks based on ‘certain patterns’ I seek to find in the answers to my research questions. I attend to patterns that signify refugees’ encounter with various borders, such as those reflecting their cross-border journeys to Lesvos and their lives within the ‘hotspots’. Then I interpret these works with perspectives from critical border studies. Overall, a qualitative analysis of artworks without any texts or speech being involved can be challenging in eliciting artists’ experiences. My positionality as a visual artist alongside this often helps me to address these challenges as it provides useful insider insights and depth of understanding in terms of making sense of the artworks that translate its maker’s lived experiences.

It has now become salient to me: the ‘visual’ offers rich insights at the intersection of art and Socio-Legal Studies. In this sense, the ‘socio’ in the ‘Socio-Legal’ proposes sufficient ground for tackling law in context through incorporating the visual as a form of data. Exploring the struggles of artmaking refugees through visual ethnography promises to expose their lived experiences and the wider social context within which law has a profound place.

An illustration from The Journey of Nasim. The text (in Turkish) from left to right reads as: ‘This is so much fun!’, ‘Hello!’