Interdisciplinary Interfaces: Theology and Law

In this contribution, Professor Mark Fathi Massoud reflects on returning to graduate school to study theology. This essay derives from Professor Massoud’s book, Shari‘a, Inshallah: Finding God in Somali Legal Politics, published in May 2021.

How does faith in God shape the collective struggle for the rule of law? To answer this question I took leave from my position as a professor of politics and legal studies to devote a year to studying theology. I enrolled in coursework at the Graduate Theological Union, in Berkeley, California. I was taught Islamic, Jewish, and Christian theology by renowned professors in the GTU’s Center for Islamic Studies, Center for Jewish Studies, and Jesuit School of Theology. Learning how theologians across Abrahamic faiths understood God was essential for me to build a theological account of the rule of law. Law school and my PhD programme did not teach me about God. So I knew that, in order to write about God, I had to learn something about God.

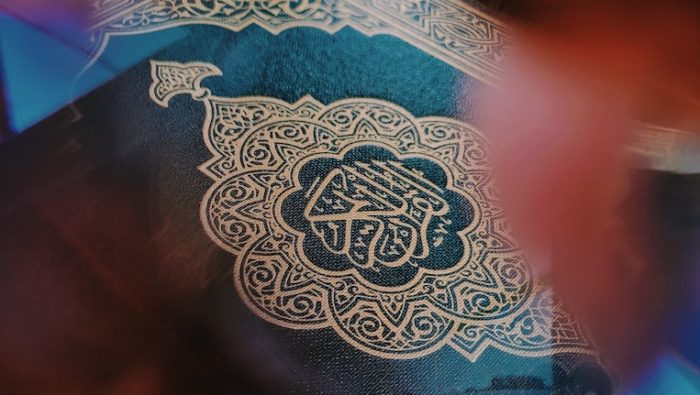

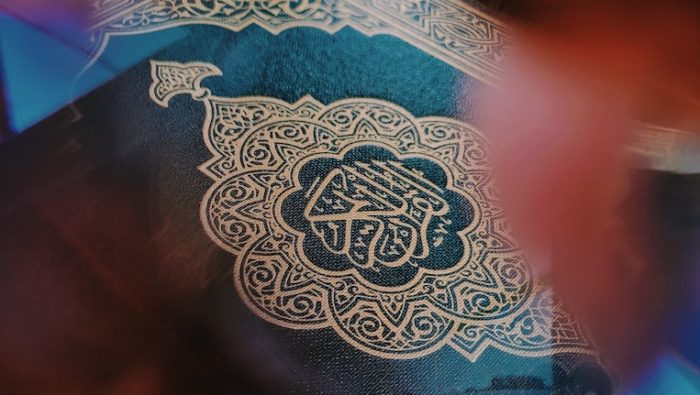

Learning theology shaped the argument that I put forward in Shari‘a, Inshallah: Finding God in Somali Legal Politics. Shari‘a, Inshallah shows how Somali activists for nearly 150 years have been invoking shari‘a (commonly translated as Islamic law) to fight for sovereignty, political freedom, and human rights. But so too have British colonial administrators, Somali dictators, and militant groups invoked shari‘a to achieve their own more reprehensible political goals. Ultimately, I argue, the zigzagging path toward the rule of law reflects not only our battles over political ideals but also our battles over God’s will.

Shari‘a, Inshallah draws on five months of ethnographic research throughout the 2010s and 142 qualitative interviews in the Horn of Africa, along with archival research in four cities in the UK. I learned during my fieldwork that foreign aid workers have concealed, marginalised, or abandoned religion, treating it as an exceptional category rather than one historically linked to the processes that develop the rule of law. My theological training helped me to see why they do this.

The very concept of the rule of law developed through a historical process that separated religion from the state. As European monarchies and state governments decoupled themselves from the authority of churches during the Enlightenment of the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, law purportedly abandoned its religious roots and traditions. By design, the law was kept at arm’s length from religious and other nonstate leaders. Religion in the European imagination began to be seen as set apart from and, over time, antithetical to the rule of law. But in culture and politics, including in secular states, religious and legal concepts have remained entwined. Political and religious leaders, for instance, regularly cite religious principles, issue commands, and invite God’s blessing.

The making of the state is a process of consolidating a multiplicity of legal orders, systems, and hopes into a single state-controlled system. The state flexes its own authority through this seemingly singular legal system that the state also portrays as pliant enough to accommodate other traditions, including religious traditions.

My book draws these conceptual, genealogical, and empirical parallels between theology and the rule of law, showing how the development of the modern state is an attempt to replace God with the rule of law.

The state was designed to treat religion as a competing worldview – even a threat – to political liberalism and its rule of law. Rhetorically freeing law from religion was purposeful. Speaking in different registers about religion and law has allowed state leaders to propound a new form of authority built on but not indentured to religious authority.

Consider the British colonial officials who roamed the Horn of Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though not Muslims, they presented a version of shari‘a to the Somali people, with the support of religious leaders from Mecca and Sudan. Colonial officials hoped that their arguments that shari‘a permitted European meddling would counteract another shari‘a that prominent Somali activists were using in anticolonial struggles.

In the twenty-first century, women activists I met embraced their shari‘a too. They used piety and strategy to try to defeat a patriarchal version of shari‘a promulgated by religious and cultural leaders.

Across the Horn of Africa’s various political epochs – colonial, democratic, and authoritarian – people have appealed to shari‘a to build the foundations of peace and the rule of law, or destroy them both.