An Unfinished Project: Japan’s Long Struggle for ‘Westernisation’

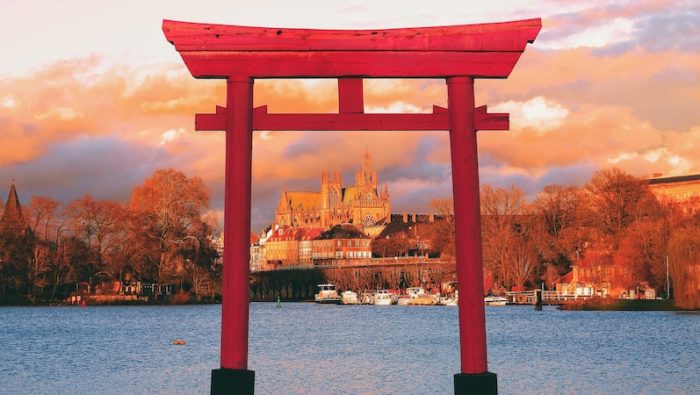

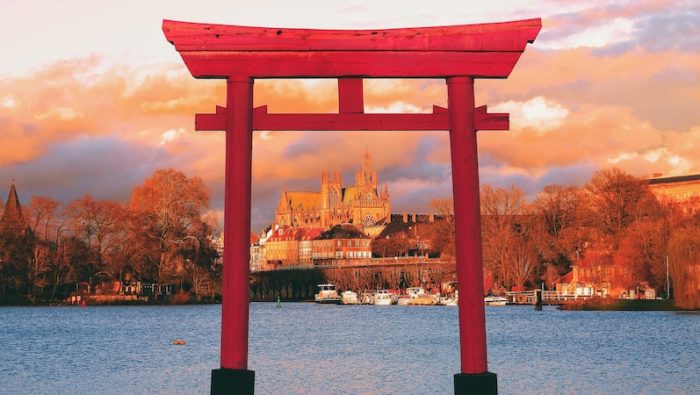

Over the past decades, the world has witnessed a remarkable number of legal transplants of ‘Western’ laws. Notwithstanding positivists’ assumption that legal transplants lead to compliance with transplanted norms, scholars have found that laws that have been transplanted rarely function as expected in the host countries. Similarly, they have found that these transplants have often been reinterpreted according to the legal culture of the recipient nation and that the degree of ‘internalisation’ of transplanted norms is crucial. In discussing the possibility of domestication, legal scholars have explored whether the ‘harmonisation’ of different laws is possible. I do not wrestle with this huge question here, but the aim of this post is to suggest a different perspective by looking at the history of Japanese modernisation. I argue that legal transplants need time—indeed, an incredibly long amount of time—. Therefore, one may need to consider the duration of legal transplants without falling into any sort of premature essentialism, which may insist on the universality or uniqueness of each legal system.

In his essay discussing the potential contribution of history to social science, Fernand Braudel, a leading historian and figure of the Annales school, claims that historians are more sensitive to ‘the weight of historical time’ than sociologists. He suggests that, while social structures are important, ‘the exact duration of these positive and negative movements’ matters in figuring out trends and patterns accurately. Indeed, the maintenance of any sophisticated legal system require significant time and resources.

I also suggest that in this long struggle procrastination has been a very sensible tactic. Japan is apparently one of the very few non-Western countries that achieved domestication of a ‘Western’ legal system, which was entirely alien to its own culture. However, it took a significant amount of time for Japan to do so since its opening to the West in 1853. Despite the prevailing narrative of the ‘rapid modernisation’ of Japan, what can be continuously observed throughout history is a form of passive resistance against the concrete changes associated with legal transplants. By combining radical changes as an official discourse with conservatism as a practical guide, Japan seems to have avoided a major backlash from its population as well as diplomatic skirmishes with the West.

When Japan was on the cusp of modernisation in the 1860’s and 70’s, driven by diplomatic needs, the government hastened to transplant a French-like legal system into every corner of the nation. However, most judges and lawyers had been educated in the atmosphere of feudal ethics and Confucianism; the concept of droits civils caused great controversy among them. In a legislative committee, the translator’s interpretation of droits civils as ‘minken (people’s power)’ made the lawmakers uneasy about what the concept actually meant. Shimpei Edoh, the Minister of Justice, settled the situation wisely by making the following recommendation ‘[n]either utilise nor kill the concept, but just leave it there. We shall have the time to utilise it someday.’ (N Hozumi, Hosoyawa (2012) at section 62, in Japanese)

Even when Gustave Boissonade, a visiting law professor from the Sorbonne, drafted the Old Civil Code a few decades later, the public understanding of Western law was, at best, inadequate. The draft became the target of a conservative political campaign in and outside the newly established parliament. Some claimed that as ‘the Civil Code appears […] Chūko (忠孝, the morality of Confucianism) extinguishes.’ (N Hodsumi, Hosoyawa (2012) at section 97) Thus, the lawyers who drafted the New Civil Code right after this incident (this time under the influence of the German legal system) adopted once again a tactic of procrastination. Although the drafters studied at Western law schools (Nobushige Hozumi, one of the drafters, was called to the bar in the Middle Temple), they did not intend to transplant Western law into Japanese reality all at once. In their view, their German-style code ‘prioritised the perfection in the eyes of Western scholars’ (p. 263) However, they knew that it would be a significant challenge for the next generations to reconcile Western law and Japanese customs. Therefore, they consciously produced a very thin code that favoured principles over rules, thus allowing wide room for interpretation. For example, the Japanese version had less than half of the 2,281 articles of the Napoleonic Code, its counterpart.

The second generation of lawyers who interpreted the Civil Code faced constant challenges. German legal doctrines dominated Japanese academia in the first half of the 20th century, before giving way to the French legal doctrines in the 1960’s, and Anglo-American scholarship in recent decades.

Even today, Japan may still have some way to go to fully appreciate droits civils. Constitutional review, which was introduced by the US in Japan after the Second World War, has been surprisingly underused. The Supreme Court was mandated to strike down legislation against the Constitution, but its notorious reticence has led to very few decisions of unconstitutionality over 75 years. Still, it is noteworthy that 7 out of twelve of these decisions happened after the turn of this century, which may imply the slow, but steady, change of the Japanese judiciary.

Laws have been transplanted and localised by a myriad of actors with various intentions in Japan, but nobody can tell whether these transplants will lead to harmonisation or diversification. The incorporation of Western laws in the Japanese legal system began 170 years ago, and we are still not in a position to foresee its far-reaching consequences over the long term.