South Africa’s Group Areas Act and Quotidian Resistance in a Small South African Town

The Group Areas Act, passed in 1952, was one of the main pillars of the apartheid project in South Africa. The Act gave life to the notorious Group Areas Board (GAB), which presided over the forced removal of people from racially mixed districts in large cities and tiny rural towns across the country. In the ensuing decades, the GAB created racially segregated residential districts, which reserved the central business districts and modern infrastructure of urban areas for whites. Forced removals, which occurred in earnest during the 1970s and 1980s, were notoriously brutal and deeply intrusive into the lives of ordinary people. But in the small town of Mokopane, which lies in the Limpopo province of South Africa, the forced removals and racial segregation of the central business district did not occur. In this post I argue that even the best organised empirical researcher needs to be prepared to change tack in the course of fieldwork and remain tenacious in their dedication to answering the questions they have posed.

The Indian merchant population (people of Indian origin, which the apartheid government referred to simply as “Indian”) that populated small towns in the Northern Transvaal, first traversed the region as itinerant merchants during the late 1800s. The Group Areas Act was, as historian Dan O’Meara writes, used as a tool to reduce the commercial threat Indian traders posed to the aspirant Afrikaner middle-class, by removing Indian traders from thriving commercial centres in urban areas to dedicated shopping centres at the urban peripheries. This forced removal famously occurred in Johannesburg where Indian traders were removed from their stores in Fourteenth Street, Vrededorp to the Oriental Plaza. But in Mokopane, the GAB did not forcibly remove Indian traders from their stores in the centre of the town. I was preoccupied with finding the reason for this when I began fieldwork.

My fieldwork produced conflicting and much more nuanced accounts than I had predicted. In interviews, some Indian traders, who owned stores in the town and who had lived through this period, said their stores remained in their historic sites because of the traders’ resistance to the GAB officials. Another affected storeowner, however, told me that he remained mystified about the reasons that the GAB abandoned its plans. He had launched legal action against the GAB and voiced his discontent at a consultation meeting convened by GAB officials. But on the face of it, neither of these actions proved conclusive and the authorities did not explain, to him or anyone else, their ultimate decision to refrain from forced removals. It became clear that I needed to look elsewhere to answer my research question.

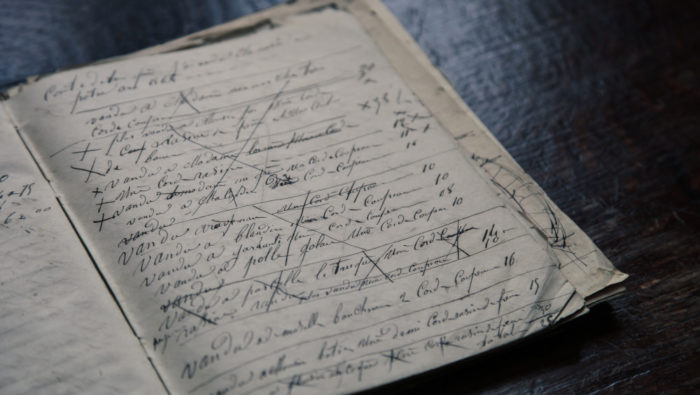

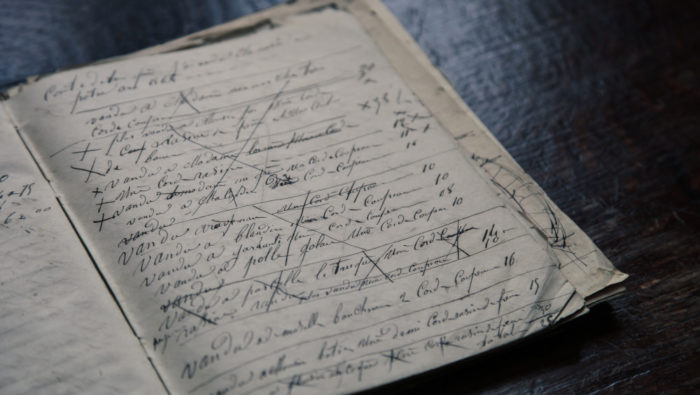

I then thought that perhaps the historical immersion of Indian traders in the socioeconomic fabric of the town was an important factor. In a letter to the government, which I found at the National Archives of South Africa, a white resident of Mokopane voiced his opposition to the removals because of his longstanding relationship with Indian traders. During times of drought, which periodically struck the district, they had extended long lines of credit to struggling farmers, and so over the years had become a part of the social life of the town. While this letter indicated the existence of less racial hostility than in the imaginary of apartheid planners, its influence on the decision-making of the GAB was unclear.

Eventually, I found the official explanation in the archives of the Mokopane municipality. The plan to move Indian traders had come to a halt because of the imperatives of a concomitant prong of the apartheid project: that of improving the economic prospects of the African homelands to facilitate their transformation into self-governing entities. The Lebowa homeland bordered the town of Mokopane and government officials believed that Indian traders would best serve shoppers from the homeland by remaining in their historic stores in the centre of town. The demarcated shopping area where the GAB planned to move the traders was too far removed from this consumer traffic.

While I was pleased at the discovery of an official explanation, I was disappointed that in the end, the machinery of the GAB remained decisive in determining action. In other words, the resistance of ordinary people was not enough to counter its might. It was nonetheless clear that the commercial success of Indian traders played a role in the government’s decision and their agency could thus be located in an area outside of outright protest; one in which their relative economic prosperity helped to overcome their political precarity in unexpected ways. This complicated the image of resistance I had at the commencement of the research, one that situated resistance exclusively within the sphere of protest politics. In order to understand the importance of residents’ quotidian activity and the social history of the town, I had to revise my initial assumptions and pursue the reason for the absence of forced removals through diverse historical sources.