Towards a Legal Theory Bazaar

How might model-making help us to respond to Margaret Davies’ call for ‘a more open, dynamic and responsive understanding of law’—one which understands theorisation less as a formalistic process aimed at conceptual unity, more as an experimental process aimed at conceptual co-existence?

To find out, I included a hands-on experiment in an Edinburgh Legal Theory Research Group seminar, ‘Unlimiting legal conceptualisation in designerly ways’. The experiment was inspired by The Futures Bazaar, a collaboration between Situation Lab and BBC User Experience and Design. It began with an invitation to ‘picture a Legal Theory Bazaar: a wild and wonderful place where all alternative [concepts] co-exist at once, and can be physically encountered in real life; a kind of multi-dimensional exchange, where tangible objects are put on offer from countless possible [theoretical] worlds’. Below are instructions for each stage of experimentation, and extracts from the post-event reflections of three of the ten participants: Sara Canduzzi, George Dick, and Tsampika Taralli.

Explore

Identify a range of Concepts of Concern—that is, concepts to which we ought to draw attention because, for example, they are foundational, contested, productive or flawed; or indeed because they are needed, but do not yet exist.

Sara and George worked collaboratively with the concept of ‘legitimacy’, and focused on ‘how legitimacy works “relationally” in both a top-down and a bottom-up manner.’ Tsampika began with the concept of ‘solidarity’, then focused down on the concept of ‘care’.

Make

Make a clay model that captures some aspect of one Concept of Concern.

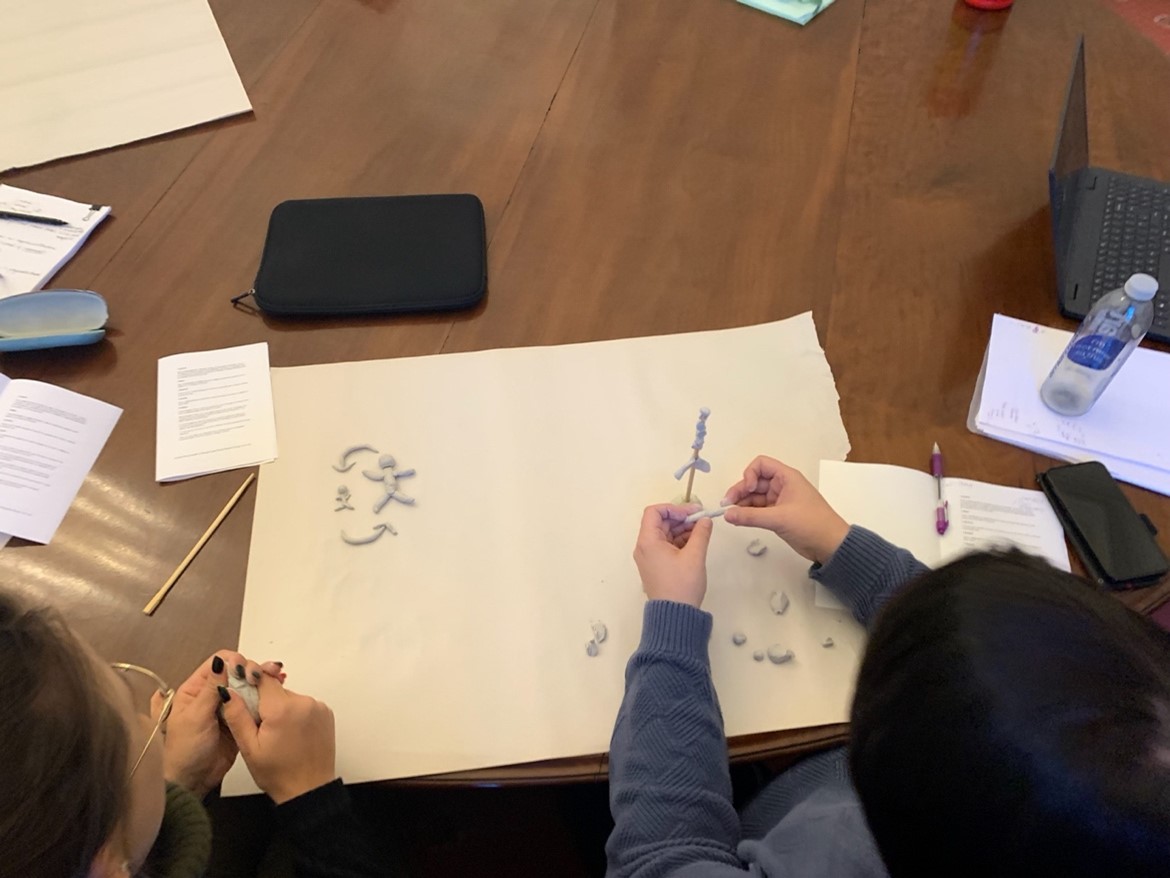

Sara and George made ‘separate models’ of legitimacy ‘to see how different people represent the same idea,’ and were struck by how different their models were (Figure 1). Sara observed: ‘My belief that arrows play a central role in my reasoning was reinforced. Whenever I visually represent my ideas, establishing connections between elements is the most productive way for me to (a) see the existing interactions and (b) carve out new ways to interpret relationships between concepts.’ For George, making ‘was the dimension I was most anxious about, as I am not skilled at creative arts. However, my clay model was a perfectly sufficient conduit for imagination and rumination.’

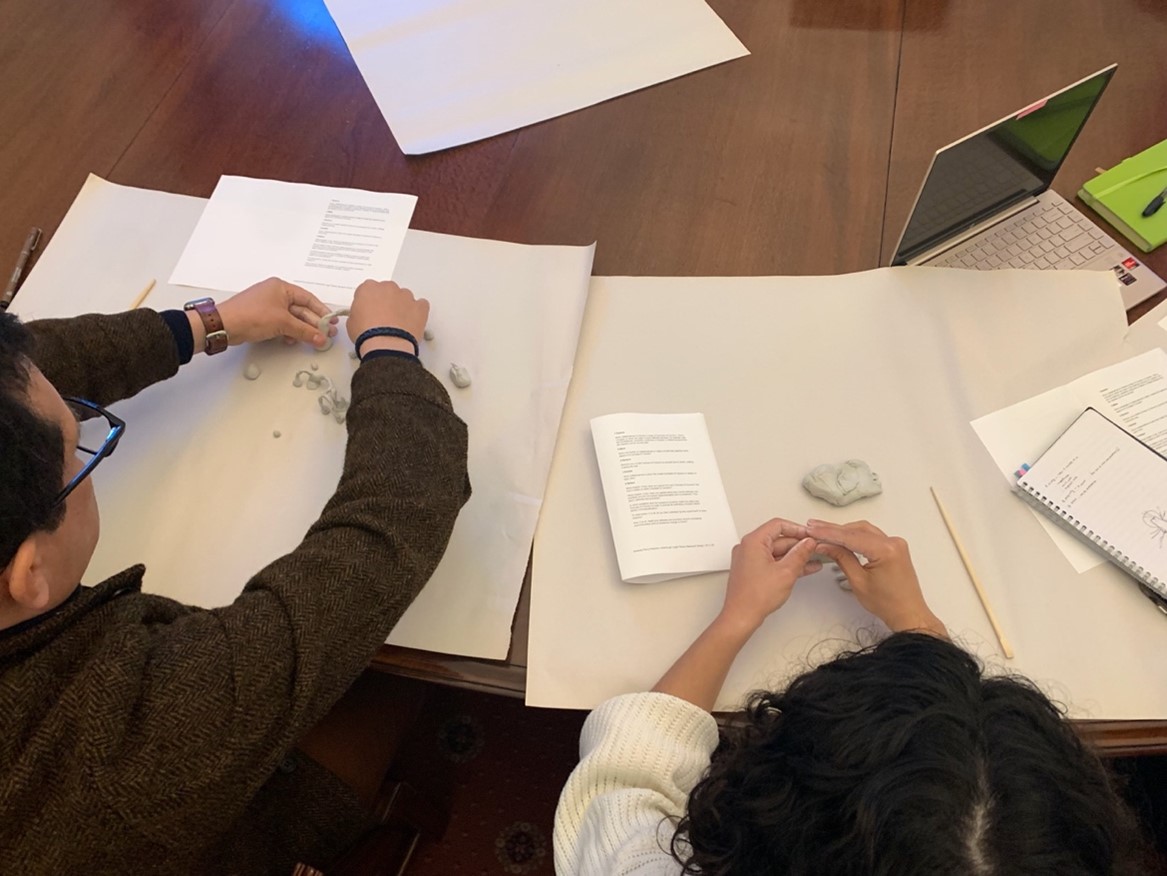

Tsampika made ‘care’ the form of a delicate hand (Figure 2). She found it ‘very interesting to see how’, when making a model, ‘we focus on one aspect of the concept.’

Figure 1: Sara Canduzzi and George Dick making ‘legitimacy’.

Figure 2: Tsampika Taralli making ‘care’.

Perform

Perform your model Concept of Concern to yourself and to others, refining it along the way.

‘Performing’ the model to the wider group ‘helped’ Sara to ‘see how I understand the relational aspect of legitimacy’, and ‘clarified why I chose to represent the concept in the way I did, why I tend to think “in concepts”, and how [this] serves me in my research.’ For George, this ‘was the most insightful aspect’ of the experiment. ‘It led me to appreciate how my unrefined little model could relate to my research on methodology,’ as well as to Sara’s on legitimacy. ‘It had more value than I initially assigned it. Perhaps it was not so inelegant after all!’ Similarly, Tsampika sensed that ‘[b]y performing our ostensibly simplistic models we discover more about the concept, and maybe what we assume about the concept.’

Exhibit

Place the Concepts of Concern in relation to each other.

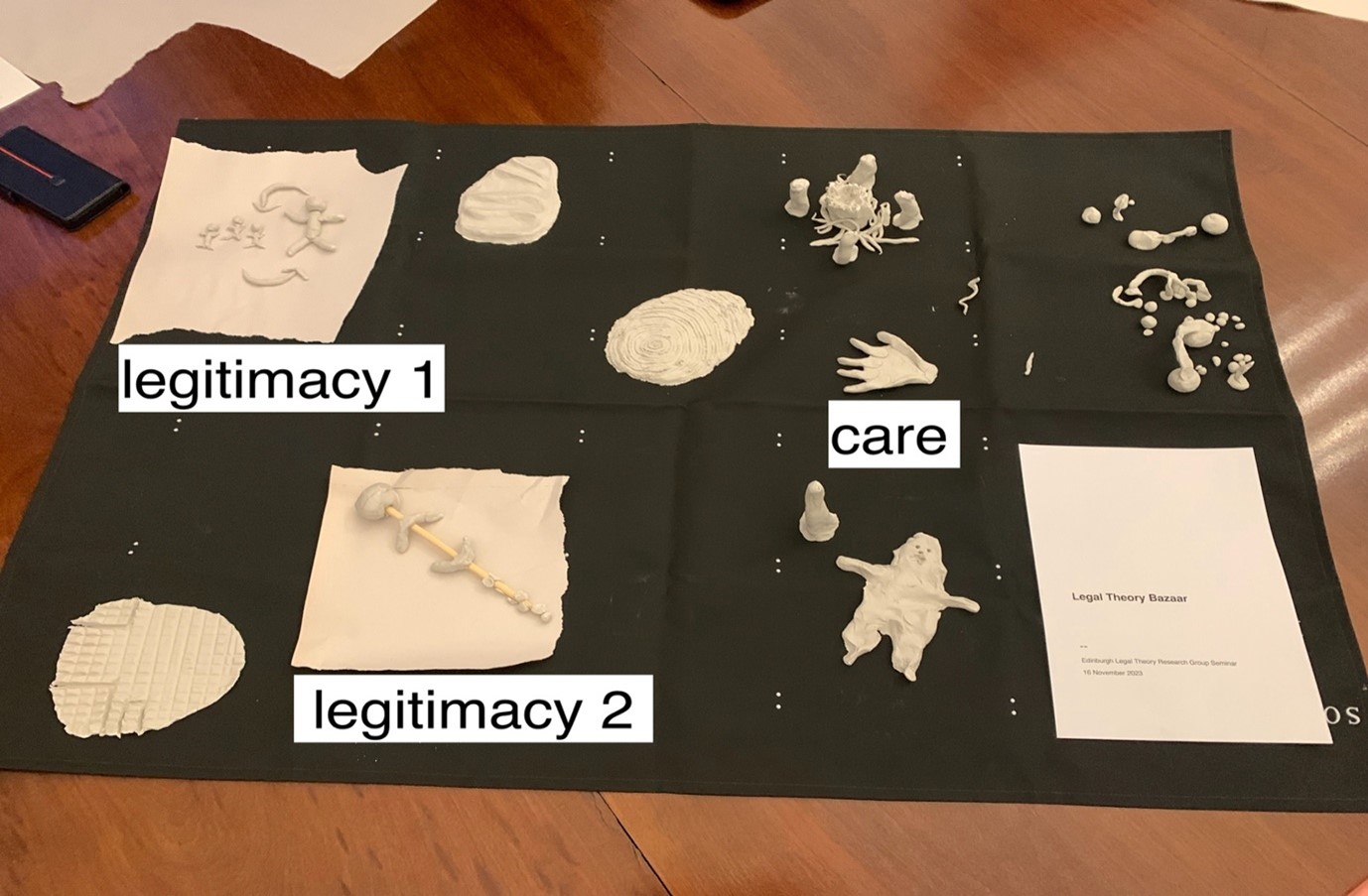

This was, for Sara, ‘probably the least revealing’ stage of the experiment ‘although I appreciate the mental effort that it elicits. I still struggle to see the connection between models rather than concepts. It remained much easier for me to think about the relations between concepts from a conceptual rather than a visual perspective.’ By contrast, for George ‘it was was neat to see what others had come up with, and how the concepts could be connected with each other’; and for Tsampika ‘[t]he visualisation of the concepts made it easier to relate and situate.’

Figure 3: Exhibition annotated to indicate Sara (legitimacy 1), George (legitimacy 2), and Tsampika’s (care) Concepts of Concern.

Reflect

Participants were asked to reflect on a range of prompts, including ‘To what extent, if at all, do you feel ‘unlimited’ by this experiment?’

George ‘felt “unlimited” by not being restricted to “armchair” thinking’ and ‘would thoroughly recommend others giving it a go, irrespective of your perceived creative abilities! I would certainly consider utilising [this method] in future.’

Sara ‘felt “limited” at first by my lack of “craft” skills, and by having to choose one dimension of legitimacy. It felt useful for understanding that specific dimension, but “limiting” in maintaining a more “holistic” perspective.’ Similarly, Tsampika felt ‘unlimited’ by the sense that ‘creating something makes you see more of what you know, but ‘limited’ by the ability to ‘visualise concepts.’ She observed that ‘[m]aybe practice will help’, and indicated that she too ‘will use this in future.’

Overall, feedback from these and other participants suggests this experiment was enjoyable and meaningful; and/but that it would benefit from refinement through repetition—both by the participants engaging in further individual experimentation, and by me organising further iterations of the experiment with different participants.

One refinement that I plan to test in several UK law schools over the coming year is to focus the experiment on legal futures. Specifically, participants will be invited to make, perform, and exhibit models representing legal concepts which are currently shaping futures, or which do not yet (or still) exist, but which might be needed in future. It is anticipated that this narrowing of substantive focus will prompt and facilitate participants to work collaboratively, and may generate new insights into the existence and implications of convergence and divergence in the practice of conceptualisation.

-

For more from Professor Perry-Kessaris in Frontiers, see her 2022 Borderlands post, ‘The Temporal Promise of Sociolegal Design‘.

-

See also, Emma Rowden’s review of Perry-Kessaris’ Doing Sociolegal Research in Design Mode (Routledge, 2022) from our A Good Read section: ‘”Designerly ways can help.“‘