Not Just for Nerds: Web-scraping as a Socio-Legal Research Tool

Web-scraping used to be considered the preserve of computer nerds. The sort of person used to arching over a computer for long hours with – as Kendall puts it – “thick-rimmed glasses and pocket protectors full of pens”. Although this author admittedly ticks those boxes, huge strides in the accessibility of web-scraping tools has now brought this research technique to the masses: as Kluwe puts it, “data mining is not for nerds anymore”.

This post is based on a recent research project examining discrimination against housing benefit recipients in the private rented sector. The project used web-scraping techniques to pull off over 30,000 pages from a leading “rooms for rent” website (SpareRoom.co.uk) for analysis. Drawing on this research, I deal here with what web-scraping is, how to do it, and why it is an important tool for a Socio-Legal researcher.

What is web-scraping?

Web-scraping (sometimes called “data mining”) is the use of software – called “spiders” or “crawlers” – to automatically pull information from large numbers of webpages. These crawlers mimic the behaviour of a real website visitor: they can click on links, navigate to pages, enter text into search boxes, and (depending on their sophistication) evade tools designed to root them out, like the familiar CAPTCHA tests. I am sure Turing would have delighted in seeing web-crawlers click the box marked “I’m not a robot”.

The systematic copying-and-pasting of others’ text may understandably raise eyebrows as a research technique. Ethical issues arise. First, scraping – particularly at a larger scale – can make considerable demands on the website owner’s resources: scraping 100,000 webpages is the equivalent of an equal number of website visitors. Indeed, this concern has led to researchers working in conjunction with the owners of the websites they seek to scrape, particularly when targeting a large number of pages. Second, most data of interest is likely to be copyrighted. In recognition of its increasingly important research role, the method has some limited exceptions under UK copyright law. For most simple projects, where the research is for a clear non-commercial purpose and adequate acknowledgement is made in the write-up, the exception applies. For my own project, the total demand on the target site was relatively low (around 32,000 total visits) and – given the clear research focus – the scraping of content falls clearly within the copyright exemption.

How Do You Do It?

Any web-scraping project has three stages. First, you design the web-crawler (a program run on your PC or a server). Second, you need to clean the data you collect (such as removing duplicates). Third, you undertake a content analysis of the listings.

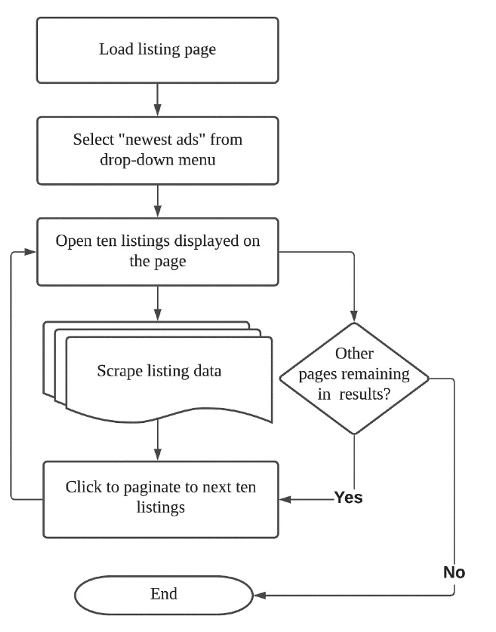

To illustrate the standard architecture of a crawler, the flowchart below depicts the crawler I used to analyse property listings on SpareRoom.co.uk. The crawler first loads a web address I provide, clicks a drop-down box, opens each property listing in another tab to download its content, then clicks to the next page until there are no more pages left to scrape.

Nowadays, no coding expertise is needed for any of these stages. The advent of a smorgasbord of “point and click” web-crawling platforms – the user interface equivalent of gesturing instructions at an assistant – means anyone anywhere can train themselves to create web-crawlers. Indeed, you can get started with many of these platforms free-of-charge and run the crawlers locally on your machines.

Why does it Matter for Socio-Legal Researchers?

This boom in the accessibility of web-scraping techniques, and exponential increases in the volume of data to mine, has led to its increasing use and interrogation as a method to help speed up some forms of legal analysis (for instance, by pulling judgments meeting certain criteria from legal databases). However, its full potential has yet to be realised in Socio-Legal studies. I think it is important for two reasons.

First, online platforms themselves are increasingly important actors in areas of interest for Socio-Legal scholars. Field and Rogers characterise this as “platform logic” – the way in which websites design and format content in turn shapes interactions with other actors. My own motivation for using a web-scraping technique was to explore how the design of a website (in this case, SpareRoom.co.uk) could in turn drive discriminatory practices against housing benefit recipients. But the role of online platforms extends to almost all works of life, from dating to consumer redress. The content on these websites therefore matters as a research focus in its own right.

Second, transparency does not mean accessibility. Even where data is available to researchers, it is often poorly formatted, difficult to access, or (in some cases, seemingly deliberately) incredibly labourious to pull-off manually. Web-scraping tools can provide the answer to the researcher thinking: “am I really going to sit and copy and paste every page I need here?”.

So, there is no need for thick-rimmed glasses and predisposition for coding. Web-scraping is not just for nerds anymore, it is accessible for everyone. And, as our interactions are increasingly mediated through online platforms, it is an important tool in a Socio-Legal researchers’ arsenal.