Yunupingu’s Song; or, What we talk about when we talk about the constitution

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following story contains images and names of people who have died.

Later this year, Australians will vote on a referendum ‘to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.’ The Voice to Parliament would provide an on-going and official channel through which an elected Indigenous consultative body would provide input to the federal government on all matters of concern. Public debate has centred somewhat predictably around legal mechanics, if not legal semantics. And media coverage has translated these arguments, again somewhat predictably, into questions of party-political point-scoring. But really what is at stake are implicit assumptions about the nature of Australians’ relationship to the Constitution itself. This requires us to leave the shallow waters of a conventional approach to law, and to replace it with a deeper sense of the relationship between law and society, including art, song, culture, and philosophy. Only a richly inter-disciplinary approach can do justice to what and how the Voice matters.

On one level, a constitution is simply a piece of legislation on steroids: a formal arrangement about the division of powers within a polity, entrenched to make it more or less difficult to modify.

But on another level, a constitution is not an act of division but an act of vision: an articulation of values, histories, and aspirations. In recent years, many constitutional scholars have argued that without some such vision, some such sense of national commitment, there would be nothing to bind citizens to the legal order other than expedience or force.

The idea that constitutions, as well as being mere textual instruments, are repositories of stories and values, is most obviously true in places like the US or France, in which the constitutional order is embedded in a narrative of struggle and progress. It is equally true in places like Germany and South Africa, where the constitution represents a critical opportunity to reckon with and break from the past. All over the world, stories of nation-building, constitution-making and revolution are constantly reinscribed through school texts, annual holidays and rituals, and pilgrimages to sacred sites.

The matter is less self-evident in Australia, where the Constitution seems to have so little to say about who we are and what we stand for. But neither it nor the judicial decisions that interpret it are devoid of a sense of Australia’s history or its trajectory, the past from which we come and the future to which we reach. It is this social and historical context that gives the constitution its power to bind us and makes it—and the referendum—something which actually matters.

The noted constitutional theorist Paul Blokker writes that if we forget this aspect of our constitutional arrangements, we put in jeopardy not their legality but their legitimacy. To focus simply on what he calls a constitution’s “formal” “rational” or “technocratic” elements is to deprive it of the narrative, values, and social practices which allow us to imbue our interpretations with meaning in different contexts and over hundreds of years. It is not just judges, politicians, or lawyers who are engaged in this process.

Constitutional experience consists of an on-going process of imagining and performing the constitutional—through fictions, metaphors, images, and conceptions—and in this depends on political imaginaries that shape and limit views of the possible, but that equally provide the basis for re-imagining the constitutional order. (p.122)

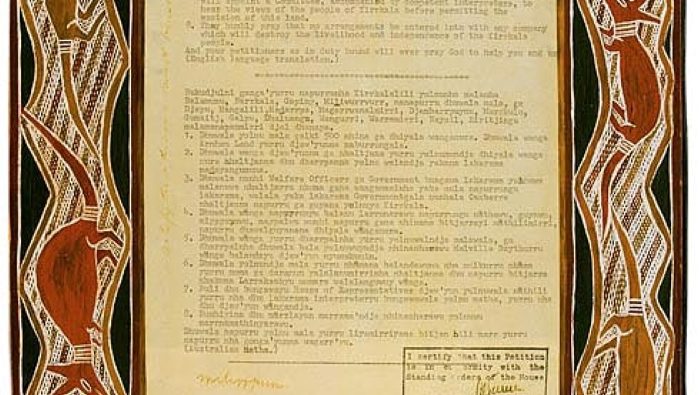

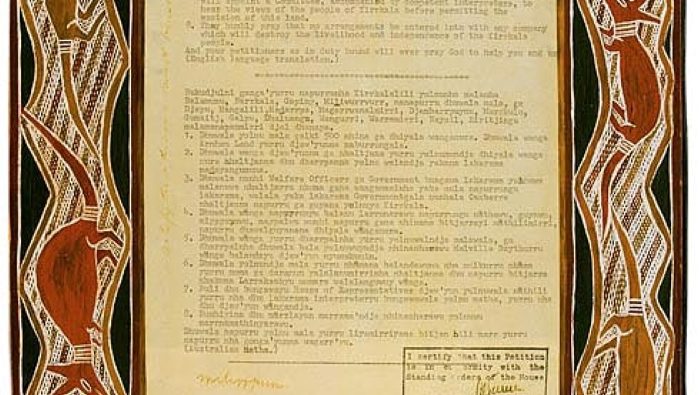

Gulurrwuy Yunupingu, the great Yolngu elder who passed away in April this year at the age of 74, understood all this very well indeed. In 1963, he was instrumental in drafting the Yirrkala Bark Petition, which presented to Parliament an eloquent claim for the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Arnhem Land before their country was, without their consent, turned into a bauxite mine. In form as well as content, the Bark Petition was radical. It was written in the language of the Yolngu, as well as in English. It was framed as a traditional petition to parliament, but likewise framed by a visual border of traditional Yolngu bark-painting. The document was an unprecedented act of cross-cultural imagination. It did not simply translate Aboriginal claims into the existing categories of Western law: it aimed to assert the independence and integrity of Indigenous law itself.

The politicians in Canberra did not know what to make of it. Nevertheless, Yirrkala was the first step in a long journey. In the 1971 Gove Land Rights case Yunupingu again demanded nothing less than a complete transformation in the way the Australian legal system understood Indigenous property rights. Another failure, perhaps: Justice Blackburn in that case categorically stated that “If ever a system could be called ‘a government of laws, and not of men,’ it is that shown in the evidence before me.” All the same, he concluded that under Australian law his hands were tied. But this cognitive dissonance unsettled our “views of the possible” and paved the way for the repudiation of terra nullius in Mabo, twenty years on. No success without failure, or rather, without the kind of failure that haunts the conscience and forces us to begin “reimagining” the fundamental principles of the legal system.

The Voice to Parliament is perhaps also haunted by a prior failure, that of the Uluru Statement from the Heart—another highly ambitious initiative in which Yunupingu, as usual, was front and centre. Like Yirrkala before it, the 2017 Uluru Statement appealed for legal change in a highly unusual tone, full of poetry and emotion. While it included specific legal proposals, of which the Voice was the most prominent, more generally it reached out across racial lines, seeking to reimagine our legal relations, precisely “from the heart” as well as with the head. Drawing inspiration from many documents, from Declaration of Independence to Bark Petition alike, the Uluru Statement called for a new affective constitution that would bind all Australians, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal alike, to it.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

If the conservative government of Malcolm Turnbull rejected this vision with indecent haste, that is because he could not see it in any terms except as disrupting the established division of power. He could not see the big picture.

What is at stake in these different ways of talking about constitutional change is the relationship between law and time. According to conventional wisdom, the question of the legitimacy of the constitution or, to put it more broadly, the ‘social contract’ between citizens and the State, is a problem that was addressed once and once only—in the moments leading up to its foundation. The problem of how to create a new legal system and do away with an old one, the problem of how to define and regulate our social relations, the problem of what moral or political content to give our legal forms, was radically open in the years leading up to the establishment of a new constitutional regime—let us say, in the case of Australia, from the Tenterfield Oration in 1889 until the passing of the Australian Constitution, an Act of the United Kingdom Parliament in 1900; or, in the case of the United States, from the Declaration of Independence in 1776 up to the ratification of the Constitution in 1787. But once a new legal regime comes into existence, those contingent and participatory opportunities, it is supposed, disappear.

But Blokker is not alone in thinking that this ‘constitutional moment’ cannot be simply relegated to the historical past. Rather, legitimacy and meaning are always and continually up for grabs; they are not an on-off switch that once flipped, runs by itself. Whether the Australian legal system and the constitution that sustains it is doing that work that Australians demand of it, and whether it is worthy of our respect and our commitment—in fact, what might be meant by ‘our’ and ‘respect’ and ‘commitment’—are questions in which we are always implicated and to which we may have very different answers. The upholding of a legal order, in other words, is an on-going task, not an historical fact. It is not enough to thank the founding fathers and move on. We are all of us responsible, every day, for the affirmation, interrogation, and development of legality.

From my admittedly limited understanding, it seems to me that Indigenous Australians have a profound and intrinsic awareness of this. Traditional Indigenous communities do not delegate law to lawyers or relegate it to the past. They consider it a collective, continuing, and everyday responsibility.

In ‘Everywhen,’ an essay published in the Griffith Review last year, Mykaela Saunders observed that Western time is linear and singular. For Aboriginal peoples, she argued, time is everywhere at once—not just time of a longer duration (65,000 years and counting), but the past and the present experienced simultaneously.

Time forever back and time forever onward lives in the land. All times are compressed and nested inside Country like sedimentary layers, and so it is inside people too. Time is inheritance: we are all embodiments of our families through bloodlines, and we personify our communities through culture. The way Aboriginal people make sense of ourselves is through our kinships, and these relationships deepen through time and across generations, accumulating stories in the process.

‘Aboriginal people talk of the past as though it is with us because it is,’ she writes. ‘For us, time is deepening and accumulating.’

One way I have come to understand this is through Aboriginal rock art, which is indicative of a multitude of cultural practices including dancing, singing, and body art. An old master like the Mona Lisa is put behind plate glass and a phalanx of security guards prevent us from getting close to it, let alone touching it. Its age separates us from it. It is not protected for us but from us. Its value is historical, not ritual. On the contrary, Indigenous rock art is older than the pyramids. But that does not mean that it has remained untouched ever since, a shrine to the past. In many cases, such art is regularly refreshed by its custodians. By repainting the art, Aboriginal people contribute to its meaning, ‘deepening’ and accumulating’ our relationship ‘through time and across generations’, rather than ossifying it or entombing it in the vaults of history. Sometimes, it may even be changed or developed in the process.

This is a very different way of understanding the relationship between past and present, between history and myth on the one hand, and the social contract of our everyday lives on the other. But it is striking how closely such an understanding parallels Blokker’s urge to consider the social contract and the constitution – not as an artefact locked in the vaults of linear time, but as a work of art whose place in the social order here and now requires present-day acts of re-affirmation and re-interpretation.

To change the point of comparison slightly, a constitution, one might say, is like an Aboriginal “songline.” It is not the record of a past event, an historical document or story that recalls what happened at a particular point in the distant past. It is a world which we are obligated to sing into existence now and every single day. The Constitution, in short, is everywhen. The Voice to Parliament, like the Uluru Statement before it, and the Gove Land Rights case before that, and the Yirrkala Bark Petition before that, and Indigenous visions of lawfulness stretching back many millennia in a wise and steady flow, is an expression of this ‘everywhen’, songlines forever being sung and re-sung—animated and reanimated, imagined and reimagined—in a never-ending collective enterprise.

What is at stake in the referendum is therefore not just specific institutional arrangements. What is at stake are two opposed ideas about the relationship between the constitution and the people. The constitution as a formal and technocratic document, held like aspic in time; or the constitution as an on-going discourse about how we need to learn to listen to one another and to talk to one another. The No vote responds to a certain way of thinking about law, time, and citizenship. The Yes vote derives from a very different way of thinking about law, time, and citizenship. It echoes ways of knowing and being with which Indigenous Australians are familiar and from which the rest of us still have much to learn.

In August 2022 at the Garma Festival, the great celebration of Yolngu life and culture held on Yunupingu’s home turf, newly elected Labor Prime Minister Anthony Albanese met Yunupingu for the last time before his death. It was there that Albanese announced the roadmap for the referendum. Yunupingu reportedly asked the Prime Minister whether he meant what he said. He would not have been the first Aboriginal leader to have his doubts about the value of the white man’s word. Albanese’s sincere commitment has something of the gravity of a deathbed promise about it. But what is at stake is not just the promises and the failures of the past. Shall we re-sing the constitution in refrains worthy of the time, or shall we lock it away in some filing cabinet, there to gather dust? A new song needs new voices to sustain it. That is what we talk about when we talk about the constitution.

A version of this discussion was published in Australian Book Review #456, September 2023.

As part of this special post, Professor Manderson’s 2023 Annual Lecture at the Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, ‘Possession Island: Queering Art, Queering Law’ can be viewed in full here: