A Model of Feminist Legal History

Traditional legal history is like traditional history used to be – a narrative of legal progress, legal institutions and famous lawmakers, inevitably male since women are such recent actors on the legal stage. Sharon Thompson’s new book Quiet Revolutionaries: The Married Women’s Association and Family Law shows how far the discipline has expanded in the other direction: it is about women – women acting together, not as powerful individuals – in an association dedicated to changing the law to improve the situation of women. Since their proposals almost all got nowhere, the book is less about what happened than about what did not happen: the reforms that were proposed, the laws we might have had but that were never enacted because the male opposition was so great – because to improve women’s situation necessarily meant making inroads into men’s privileges.

Quiet Revolutionaries offers a new perspective on the pursuit of sex equality that so dominates modern feminist thinking, at the same time correcting a misreading of feminism as always and only concerned with equal rights in the workplace and public life. The Married Women’s Association (MWA) represented a different perspective: they sought an ‘equal partnership’ in marriage through shared access to the marital property and earnings. Their target beneficiaries were housewives, for the simple reason that in 1938 when the association was founded, and throughout the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, when they lobbied the lawmakers, most women were housewives. And being a housewife, with little or no income or property of her own, put a woman in a precarious position should her husband die, leave, or refuse to share. It still does. Thus, without the financial means to rebel, or often without alternative choices, the great majority of one sex could be rendered powerless, under the control of the other sex.

English law recognised no system of shared marital property (and still does not), which meant that the great feminist achievement of the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882 was more symbolic than material: it enabled married women to keep their own property but was of little use to a woman who had none. Of course, English husbands were supposed to support their wives and families: some did, some did not, and some were parsimonious in the level of support they gave. The MWA recognised all too clearly that property is power, and that without means of their own, housewives were vulnerable to exploitation of every sort. The book tells the (quite forgotten) story of the MWA’s activities: the cases they publicised, the representations they made to legal bodies, the bills they drafted, the few that were debated in Parliament and the one statutory success. It explores why this type of feminism was dismissed by later feminists and historians as ‘not feminist’ at all because the association did not challenge women’s relegation to the home or oppose marriage as the root of women’s oppression. It tells of actors within the movement and supporters outside it but, most tellingly, it reveals the strength of the male opposition, their reluctance to concede joint ownership of the home or income or even a legally enforceable share of the ‘family wage’.

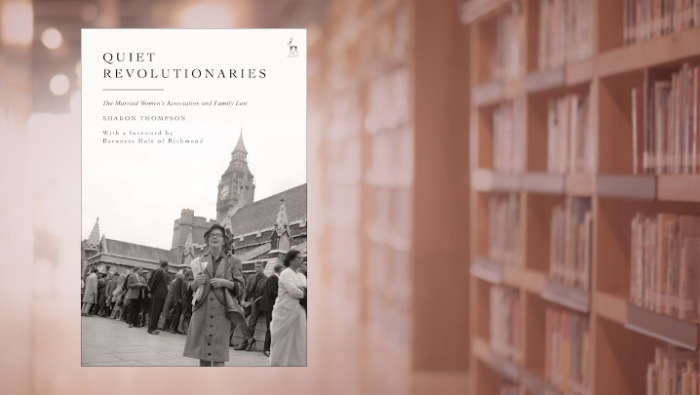

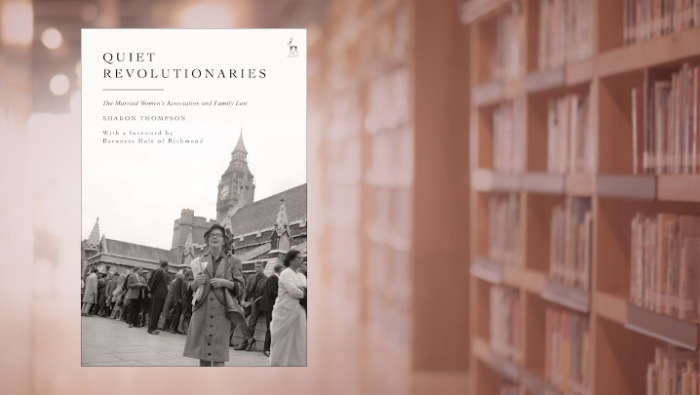

Original in argument, the book is also original in structure. Interspersed throughout the largely chronological narrative are ‘interludes’ focusing on individuals, not all of them heroes in this account. The cover picture is arresting, and there is a foreword by Brenda Hale (herself a chronicler of women’s legal history) that speaks for itself. As she points out, ‘the idea of equal sharing during the marriage seems as far away as ever’.

The book is beautifully written, providing the reader with a real sense of what it was like for women (and men) in previous decades, for Thompson has done her research in archives and from interviews and knows the period thoroughly. What it also offers is a properly accurate and nuanced examination of the law and the proposed reforms that one could only get from an experienced teacher of both family law and property law. Quiet Revolutionaries takes feminist legal history – and legal history generally – to a new level.

Further listening: Professor Rosemary Auchmuty on feminist legal biography